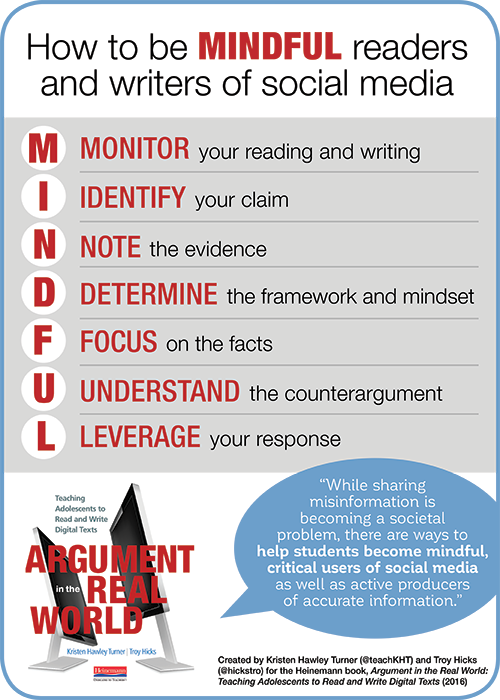

Based on the book that I wrote with Kristen Hawley Turner, Argument in the Real World, one of the tools/strategies that I have been sharing in workshops this past year is the “MINDFUL” heuristic for readers and writers as they engage in academic arguments with, through, and about social media.

When we were wrapping up the book in early 2016, even before “fake news” and “alternative facts” became a phenomenon, Kristen and I designed this heuristic to fill in the gaps that we felt existing website evaluation checklists were missing.

In short, those checklists and other tools were created in the early days of the web when we – as educators and information consumers – generally placed the onus of responsibility on the creator for being accurate. This, of course, was a holdover from our view of the printed word having gone through extensive review and editing in order to be published. The power of books, periodicals, encyclopedias and similar sources came from the fact that they were curated by experts.

Yet, with the abundance of material emerging on the information superhighway, educators, especially librarians, knew that careful editing and peer review weren’t happening all the time. We needed to create a way for students to understand that some creators were thoughtful and accurate, while others were misleading or creating an outright hoax. So, we held those creators to task by engaging with such checklists as readers so we could bring a critical eye to what we were reading/viewing. We also encouraged students to never trust a blog, or Wikipedia, or other sources that were not well-vetted. (Of course, we have since changed our tune. A bit).

At any rate, website evaluation checklists worked okay, for a while at least.

However, this was before the vast majority of us became content creators in the Web 2.0 era. Blogs, wikis, and other forms of media were being created at a constant pace and, unfortunately, with different audiences, purposes, and degrees of veracity.

More recently, through social media, we are all creators, curators and circulators. Our roles as writers have changed. The role of the reader – as someone with agency and perspective in the online reading and writing process – also needed to take responsibility for the types of arguments being created and perpetuated.

What Kristen and I wanted to do, then, was to rethink this instructional strategy of website evaluation. We came from the stance of helping students –as both readers and writers of social media – to recognize that (borrowing from Lunsford, Ruszkiewicz, and Walters’ book title) everything is, indeed, an argument.

Retweets and likes are, despite the disclaimers, endorsements. And, by extension, arguments. The way that we see evidence presented in social media matters because it will inform our own stance, as well as the perspectives of others with whom we engage. We create arguments through the act of liking, retweeting, reblogging, or otherwise endorsing, let alone when we create our own updates, tweets, or blog posts.

Rethinking the traditional website evaluation tool meant that we need to consider the challenges that new media, new epistemologies, and new perspectives all bring. In other words, it was no longer enough to simply read the “about” page, do a WHOIS lookup, or even try to understand more about the language/discourse being used on the page/post.

We needed something different. Hence, MINDFUL.

We wanted to help teachers, in turn, help their students slow down just a bit – even a nano second before retweeting, or a few moments when crafting an entire post – and to think about how arguments in digital spaces are constructed, circulated, and perpetuated.

I think that MINDFUL is helpful in doing just that. Below, you will find slides that I have been using over the past few months as well as links to additional resources I discuss in the presentation.

[googleapps domain=”docs” dir=”presentation/d/e/2PACX-1vTIBgDI7jh-J0IxyWDO-PFmKMJ30VE9v8Wi25hfL5kgj-m49GuD_WA2JT5Oenggk2pBWIQMKzjlCFH2/embed” query=”start=false&loop=false&delayms=3000″ width=”480″ height=”389″ /]

Additional Resources

- Argument in the Real World Wiki

- Our post on the Heinemann blog: Seriously? Seriously. The Importance of Teaching Reading and Writing in Social Media

- For the MINDFUL elements

- Monitoring our own reading and writing means that we must be aware of and account for Confirmation Bias. Of course, helping students (and ourselves) to do that requires a number of strategies, which are outlined in the rest of the heuristic.

- Identifying the claim means that we must separate the opinions that someone offers from the facts that may (or may not) support the claim. A refresher on Fact vs Opinion from Cub Reporters is a useful place to begin, even for adults.

- Noting the type of evidence and how it supports the claim is useful. As a way to think through different types of evidence – In the claims they can support – it is worth taking a look at the Mathematica Policy Research Report “Understanding Types of Evidence: A Guide for Educators“

- Determining the framework/mindset is perhaps one of the most difficult elements for anyone, especially children and teenagers, to fully understand and accomplish. Without taking a full course of study in critical discourse analysis, a few resources that are helpful include the idea of Sam Wineburg’s (of the Stanford History Education Group) idea of “reading laterally,” explained here by Michael Caulfied. Also, using sites like Allsides, Opposing Viewpoints in Context, and Room for Debate can help. Finally, there is the Media Bias Fact Check plugin for Chrome and Firefox (which, of course, has some bias, and questionable authorship). But, it’s a start.

- Focusing on the facts requires us to check and double check in the ways that researchers and journalists would. Despite claims to the contrary from those on the fringes, sites like Snopes, Politifact, and FactCheck are generally considered to be neutral and present evidence in an objective manner. Also, there are lots of objective datasets and reports from Pew Research.

- Understanding the counterargument is more than just seeing someone else’s perspective and empathizing/disagreeing. We need to help students understand that arguments may not even be constructed on the same concept of information/evidence and in fact some of it could be one of the 7 Types of Mis- and Disinformation from First Draft News.

- Finally, leveraging one’s own response is critical. Understanding the way that fake news and other propaganda is constructed and circulated will help us make sure that we do not fall into the same traps as writers WNYC’s On the Media provides a Breaking News Consumers Handbook for Fake News that is, of course, helpful for us as readers and viewers, but could also be a guide for what not to do as a writer.

My hope is that these websites/resources are helpful for teachers and students as they continue to be mindful readers and writers of social media.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.