As the new semester begins, many faculty are again engaged in an ethical debate about the ways in which their students might use AI in their writing assignments, whether with explicit guidance and permission, or otherwise.

This past week, I was invited to join educational futurist Bryan Alexander and my colleague and collaborator Daniel Ernst as we discussed a number of ideas related to AI and the teaching of writing at the college level. It was a robust discussion, and I encourage you to view the Future Trends Forum recording here.

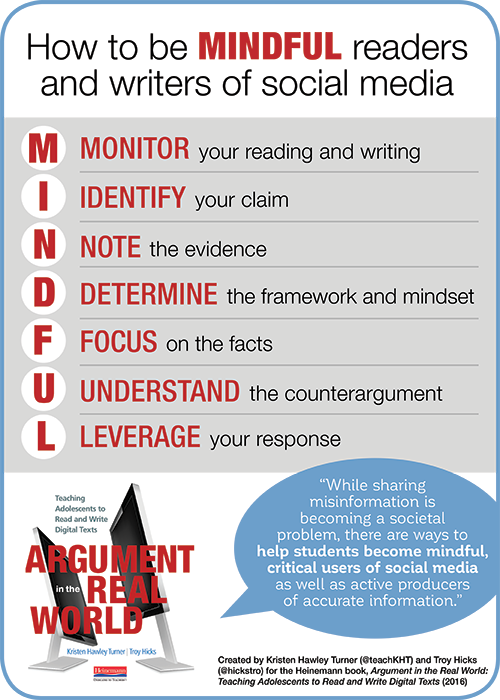

Over the past few months — as I have been trying to refine my own thinking on AI and writing through blogging, facilitating workshops and webinars, beginning a new book project with my colleague and co-author Kristen Hawley Turner, and reviewing the transcripts of our focus group interviews from the project Daniel and I have been working on — I have begun to summarize the ways in which my colleagues are describing their use of AI in writing instruction in the following manner.

In short, I am hearing educators talk about and seeing ways that AI can serve 1) as a thinking partner, 2) as a research assistant, and 3) as a co-writer. This is an imperfect list, of course, as the tools continue to change. Yet, as 2024 begins and the range of functions available in generative AI writing tools seems to be settling into a few categories, I share some initial thinking on them here.

AI as Thinking Partner

With the many AI tools that students can use as conversational partners (e.g., ChatGPT, Bing, Bard), I wonder how we can encourage them to engage with the AI as a thinking partner, much the same way we would during a writing conference (or encourage them to interact with peers to share ideas and give feedback). How might we encourage students not to simply ask the chatbot to write an essay or story for them, and instead to prompt it for the kinds of feedback that could further their own writing?

For instance, when prompting ChatGPT in this manner — “Given recent weather patterns, I am getting more worried about changes to our environment, and I am working on an argumentative essay on climate change. What are some questions that could help get me started as I think about specific topics to cover in my essay related to sea level change, heat waves, and forest fires?” — it provided me with a decent list of questions that could lead my writing in additional directions.

Similarly, Bard’s Copilot (which I have access to through my institution’s Microsoft license) generated some questions, though perhaps not as nuanced as ChatGPT’s. As just one example, Chat GPT generated “How has the global sea level changed over the past few decades, and what are the primary contributors to this change?” whereas Copilot asked two separate questions “What are the primary causes of sea level change?” and “What are some of the most significant sea level changes observed in the last decade?”

Even having students compare the outputs of these AI tools could be useful, looking at the depth and nuance evident in the questions, and thinking about which set of questions would lead to more substantive, engaging writing. Even if just being used to prompt thinking, encouraging students to use the AI chat tools as a way to develop new inquiry questions is one way to engage with AI as a thinking partner.

Of note, both ChatGPT and Bing provided a similar set of caveats at the end of their output, which are somewhat helpful reminders (if followed by additional instruction and coaching). Here is ChatGPT’s:

“Considering these questions can help you delve into specific aspects of each topic and provide a well-rounded perspective in your argumentative essay on climate change. Remember to back your arguments with credible sources and evidence to strengthen your case.”

ChatGPT Output

On a related note, Paul Allison has been doing a good deal of work to integrate specific GPTs for feedback and scaffolding thinking in NowComment. This is certainly a tool that is worth exploring as we help students engage in substantive dialogue around texts, images, and videos, all supported by scaffolded thinking via GPTs that are customized to specific academic tasks.

AI as Research Assistant

As tools Perplexity, Bing, and Bard continue to integrate sources into the AI output and fight many of the fears about hallucinations and misinformation that have been part of the AI conversation since the fall of 2022, I have begun to wonder what this means for students in their efforts to critically evaluate online sources. In this sense, the AI output itself is one source, as well as the additional sources that are referenced in these outputs.

For instance, in a search for “What is climate change?” via Perplexity, it yielded links to six additional sources in the first sentence, with a total of eight different sources for the article. It produced a clear, concise summary and prompted additional questions that the user could click on and explore. By comparison, a Google search of the same question (and, yes, I know that we aren’t supposed to ask Google questions, yet it is clear that many people do), provided a list of sources and a summary panel from the United Nations.

Of note, it is interesting to see that Perplexity’s sources (UN, two from NASA, World Bank, NRDC, NatGeo, Wikipedia, and BBC, in that order ) are similar to, though not exactly the same as Google’s output in the top ten hits, for me at least: UN, NASA, World Bank, NASA Climate Kids, BBC, NatGeo, US EPA, NASA, Wikipedia, and NRDC, in that order. This, of course, could lead to some great conversations about lateral reading, tracking of user data across the web and privacy, and the ways in which different tools (traditional search as compared to AI-powered search) function.

Moreover, as we begin to see AI embedded directly in word processing tools, this research process will become even more seamless. And, as described in the section below, we will also want to begin thinking about when, why, and how we ask students to engage with AI as a co-writer, relying on the research it has provided to craft our own arguments.

AI as Co-Writer

Finally, the aspect of AI in English language arts instruction that I think is still causing most of us to question both what we do, as teachers, and why we do it, is this idea that AI will take over anything from a small portion to a large degree of our students’ writing process. In addition to the initial fear of rampant, outright cheating and how to catch plagiarists, in conversations with my colleague Pearl Ratunil of Harper College, we are trying to understand more about how AI cuts to the core of who we are as teachers of writing. Teaching writing, in this sense, is deeply emotional work, as we invest time and energy into the success of individual writers, providing them with coaching and feedback. To think, feel, or actually know that they have undermined our efforts at relationship-building, let along teaching specific skills that are then outsourced to AI is, well, deeply saddening.

Yet, back to the main idea here of AI as co-writer. The tools are here, becoming more and more integrated and our student will continue to have access to and use them in their day-to-day writing tasks. I learned about another new-to-me tool the other day, Lex, and that is on my agenda to explore in the weeks ahead. Add that to the list of many tools I keep exploring like Rytr, Wordtune, Quillbot, and more. Lex claims that “With Lex’s built-in AI, the first draft process becomes a joy. No more switching back and forth between ChatGPT and Google Docs,” so that will be interesting to see.

More than simply an auto-complete, these tools do have the capability to help students explore genre and tone, adjusting messages to different audiences based on needs for style and clarity. Just as we would want students to be capable writers using other tools that they have available to them — both technical tools like spelling and grammar checks, as well as intellectual tools like mentor texts and sentence templates — we need to help them make wise, informed decisions about when, why, and how AI can help them as writers (and when to rely on their own instincts, word choice, and voice).

As Kristen Turner and I work on the book this year, I will be curious to see how some of these tools perform to help support different, specific writing skills (e.g., developing a claim or adding evidence). My sense so far is that AI can still help produce generic words, phrases, sentences, and paragraphs, and that it will take a skilled writer (and teacher) to help students understand what they need to revise and refine in the process of writing.

Closing Notes

In my “welcome back” email to faculty this week, I shared the following as it relates to academic integrity issues.

Having had conversations about this with a few of you last fall – and knowing that a few of you dealt with cases of potential AI dishonesty – as we begin this semester, it is worth revisiting any policies that you have in your syllabus related to academic honesty and AI. It is no surprise that I am still, generally, an advocate for AI (with some guardrails), as our own students will need to know how to use it in their professional communication, lesson planning, and in teaching their own students to use AI tools.

In addition to the many resources on the CIS AI website, one that they have listed is from Dr. Christopher Heard of Pepperdine/Seaver College, who used Twine to create an interactive where you can create a draft of syllabus language that is then free to use and remix because it is in the public domain. This tool could be a useful start, and I would also encourage you to read recent research on the ways that AI plagiarism detection tools are, or are not, doing so well at the task, and that many are biased toward our multilingual learners, the use of AI detection is perhaps dwindling, as some universities are simply abandoning the tools altogether. If we do plan to use plagiarism detection tools at all in our classes, then we need to follow best practices in scaffolding the use of such tools and making students aware of our intentions.

Finally, consider this student’s perspective in an op-ed for CNN, who encouraged teachers in this manner:

“We can be taught how to make effective prompts to elicit helpful feedback, ideas and writing. Imagine the educational benefits students can gain by incorporating AI in the classroom, thoughtfully and strategically.”

Sidhi Dhanda, September 16, 2023

As we focus more intently this semester on core teaching practices, I will be curious to see where the conversations about the use of AI intersect with our goal to prepare the next generation of teachers.

Throughout it all — as I keep thinking about AI in the role of Thinking Partner, Research Assistant, and Co-Writer — 2024 promises to be another year dominated by the conversations around AI. In the next few weeks, I have at least three professional development/conference sessions on the topic, and I am sure that we will revisit it during our upcoming MediaEd Institute and summer workshops with the Chippewa River Writing Project, as well as the faculty learning community I am participating in at CMU.

In what ways are you rethinking the teaching of writing in 2024 with the use of generative AI writing tools?

Photo by Aman Upadhyay on Unsplash.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Earlier today, I was honored to be invited by

Earlier today, I was honored to be invited by