In response to one of my earlier posts this week, Will Richardson asked:

So without going down the rabbit hole completely, how do you decide what feeds to read, which Flipboard magazines to sub, which Twitter users to trust enough to follow, etc.? It seems like there’s a whole ‘nother layer to “preparing to read” that used to be provided by editors, reporters, authors, et al who came with a built in reputation of trust. How do we assign trust in an easy-to-publish world where everyone can create and contribute?

As always, Will asks great questions and I have been mulling this over since yesterday. Let me start a reply by backing up one step, then jumping into that rabbit hole.

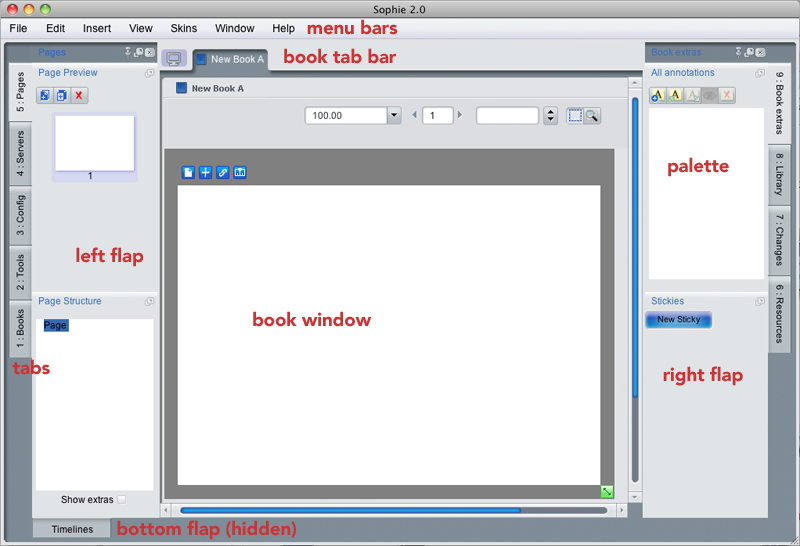

What is Digital Reading Comprehension?

First, much of the literature on reading comprehension and the Internet has relied on the fact the most people begin reading online by doing a search. That is, most studies look at how students go about searching to begin with, how they choose to click on those search results once they appear, and how they evaluate the credibility of the webpages that they find. This is good work, and Julie Coiro is the person I trust the most when it comes to looking at online reading comprehension. It’s important to know when, how, and why people look at search results and then continue in a hyperlinked reading experience.

That said, while looking at how students evaluate search engine results and the credibility of individual web pages is a perfectly reasonable and smart approach, it is not the only approach to reading digital texts. Will and his colleagues at PLP have documented time and again the many ways that we can connect and learn online through social networks. That is, we don’t necessarily go searching for things by starting at Google, Yahoo, or Bing.

Instead, we have others send us stuff (sometimes when we ask for it, often times through “passive” search on our own social networks, and, as is the case with emails from that one annoying friend or family member, when we don’t want it at all). This is not necessarily objective and neutral information from credible sources. Instead, we get caught in our “filter bubbles” and are likely to read and view many of the same texts that others with our same ideologies share via FB, Twitter, etc.

So, what does this mean for us — and our students — as digital readers?

Curating the Curators

First, I think we need to turn the tables on how we go about finding digital reading material. We need to curate the curators, both machine and man.

Yes, the Internet search has been and will remain a key way of finding new information on a topic. However, we can also teach kids to be strategic in finding curated material, via RSS, from smart and thoughtful people, but making that our own.

In some ways, is the difference between going to the library and simply looking for a book as compared to going to the library and talking with the librarian about a topic. If we teach kids (and ourselves) multiple ways to find good information, it is much more likely that they will find diverse perspectives as well as credible information. With the Internet, surely there are at least two sides to every story, and probably hundreds more.

Second, to fall down Will’s rabbit hole of a question, I would say that my own decision-making process is guided by two primary means, and then a number of secondary strategies.

Number one, I begin by looking for the topics I am interested in and will simply trust, for better or worse, the curated material that others have presented. Similarly, I will trust someone who has many followers on Twitter and also produces a variety of good tweets that include links, strategies, and helpful interactions. Perhaps this is a bit naive, as some people have millions of followers and produce nothing worth reading (the old, “what I ate for breakfast” blogging problem). In this sense, Twitter is not another form of entertainment for me; instead it is a source for personal and professional knowledge. If someone is just advertising a product or into shameless self-promotion, then I am not interested in following him/her.

The second way that I do this (and I admit that it takes time and doesn’t always work out) is that I follow some of the trails and see where they are going. For instance, if a colleague on Twitter for trust mentions another person and the context of the tweet suggests that I might want to follow him/her, that I will click on his/her twitter feed and take a peek at it. This whole process takes me anywhere from about 10 to 30 seconds, which doesn’t sound like much but really is an investment of time.

Similarly, when using a tool like Flipboard, if I see that story has risen to be “popular” or the app has automatically suggested another content feed for me, then I will peek out at it briefly. If it appears to be good, then I will subscribe. I have to trust the wisdom of the crowd, just as I would trust a good librarian. Yes, sometimes the crowd leads me astray (I could certainly benefit by decluttering my Twitter feed), but the fact is that I am a highly motivated reader with the ability to skim and determine importance. If I see something that is not useful, I breeze by, and the amount of good reading material that I get from my PLN far outweighs the bad.

Other Digital Reading Strategies

Another strategy is that I pace myself with the feeds. For instance, I may open up my Feedly to look at news from Central Michigan University, but I usually only do the about once a week. I simply don’t need to keep up on it every day.

On the other hand, the folder in my Feedly for edubloggers is something I check quite often, usually about every other day so I can scroll back through the last 48 hours of headlines. Over the course of an entire week, I may spend about an hour in Feedly and an hour in Flipboard, each of which may launch me into another hour or so of linked reading.

I also get those regular e-mails and my main twitter feed, which may also each result in another hour or so of reading. The rest, quite honestly, it’s just browsing to make sure that I am catching the major headlines both from more formal journalistic sources as well as my PLN.

During this reading time each week, I will likely find some new sources that — because they are being recommended by existing colleagues and edubloggers that I follow — I will, as Will states, “assign trust” to and begin to follow. Now, this doesn’t happen every week, as I have plenty of feeds to keep track of. In fact, it probably happens about once every month or two that I pick up a new blog feed that I really want to stay on top of. In that sense, my digital reading practices are, paradoxically, quite slow.

Lastly, it is often the case that I may see something in one of my feeds and not click on it at that moment, only to find that — two or three days later — I find myself googling for an article that I barely read member seen the headline. For instance, this week, I know through both my twitter feed and one of the e-mail updates that there was a major article about Murdoch, Klein, and the Amplify tablet in the New York Times. I didn’t have time to read it the other day, but I did catch the headline, I was able to quickly find it this morning.

As I think about how my digital reading strategies align with the tried and true comprehension strategies I listed the other day, I see some cross over as well as some areas that are distinctly different:

| Activating background knowledge

|

- Carefully building my RSS feeds and PLN to reflect my needs and interests, as well as opposing opinion

- Setting up Google Alerts to be notified of certain names and terms that appear in the news or scholarly publications

- Approaching my reading (Feedly, Flipboard, Twitter) intentionally each day

|

| Questioning the text

|

- Clicking on links to see original sources

- Taking notes and pulling out quotes

- Reading four ways: upon, within, beyond, against

|

| Drawing inferences

|

- Knowing the background and slant of the writer, his/her history as a reporter/blogger/scholar

- Understanding the context in which the work is published (own blog, organizational blog, scholarly journal)

|

| Determining importance

|

- Skimming and scanning major headlines and stories to determine importance for me as a reader

- Searching within the document for key words (Ctrl+F)

- Checking other sources that the author cites

|

| Making mental images

|

- NOTE: this is not so much a comprehension strategy I use with non-fiction, both because it really is something that lends itself to narrative and because many non-fiction pieces are supplemented with audio, video, or images

|

| Repairing understanding

|

- Right-clicking to bring up the dictionary if I encounter and unfamiliar word

- Searching within the document for the first instance of a term if I missed it in my original reading

- Jumping to the end and seeing which citations are used for which rhetorical effect

- Clicking back on a previous link

- Clicking ahead on a link to see why an author included it, then returning to read that article after finishing my reading of the first one

|

| Synthesizing information

|

- Writing

- Writing

- Writing

- Seriously, I write. A lot. Through my notes in Zotero, condensing ideas into Tweets, writing my own blog, comments on other blogs, and (of course) scholarly writing for articles and books. Writing is the best way for me to synthesize reading.

|

Conclusion

All of this is just to say that I do make a very conscious effort to curate even what has already been curated for me. There is no way to keep on top of everything, and I don’t even pretend to try.

Over the course of the past 10 years or so, as I have learned to use RSS (and, yes, Will’s original blog was the first one that I followed with my original Bloglines account!), I have pulled together feeds that are useful for me. Twitter has, to some extent, supplanted that. I try to keep a “balanced” reading list, inviting some RSS sources that will, I know, help me see beyond my own filter bubble.

Moreover, I actively use and adjust my online comprehension strategies so I can make meaning as I go. Often, as I wrote yesterday, that means finding key quotes and staying with one article (web-based or PDF) before clicking off to read something else. That takes a very conscious, active effort on my part, as the natural tendency is to keep clicking.

I don’t know that I am any closer to digging myself out of the rabbit hole. I don’t know that I, or any of us, ever will be. Still, IMHO, I have a good lantern and all the other caving tools that I need to keep exploring as a digital reader. I hope that Kristen and I can figure out how to summarize and share these strategies in a way that is most helpful for teachers and students.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Like this:

Like Loading...