This post was originally published on the Sweetland Digital Rhetoric Collaborative blog on January 21, 2014.

Our post last week looked up an example of a basic ebook, one that is essentially a PDF document or ePub style and has features such as search and annotation, adjustments for readability, and the ability to access some other functions of a tablet such as a web browser. This week, we will look at ebooks with increasing levels of interactivity, beginning today with enhanced ebooks.

Enhanced eBook Features

As Avi Itzkovitch describes them, enhanced ebooks “are a new digital publication standard that allows easy integration of video, audio, and interactivity.” This can include options such as richer annotation features, quizzes, audio and video content, and links to supplemental content available on the web. While this type of interactivity enhances an ebook, I would argue that these features may still not contribute to the overall meaning making process for a reader in significant ways. In other words, simply because the digital writer may create a text using a tool such as iBooks Author, this does not necessarily mean that the content provided contribute to a reader’s comprehension or enjoyment of the book without careful attention to detail.

That said, making an enhanced ebook could, of course, contribute to a richer comprehension and enjoyment process. For instance, a text could be created as an interactive adventure, or having the reader to engage in one of the interactive features could reveal a crucial plot development or piece of information about a topic. Still, for the most part, these multimedia components or hyperlinks merely reinforce or complement the existing textual material. Ideally, this is not just interactivity for its own sake. An e-book that has some interactivity and multimedia features should bring something more to the reading experience than only reading text alone.

Enhanced eBook Examples

Given that my particular interest is in K-12 education and how teachers can help their students become digital readers and writers, I wanted to look for examples that they could use as “digital mentor texts.” This is a term that some colleagues and I coined for a series of blog posts in the beginning of 2012. By this, we were hoping to move the conversation about “mentor texts” — those exemplary stories, poems, articles, or even single sentences or paragraphs we can use as models for our students — and think about what types of digital writing could be used as mentors. Thus, I want to carry on in that fashion and look for some examples that could become the types of enhanced e-books that K-12 students could compose.

First, I might suggest building a “choose your own adventure” style book. Of course, there are our old favorites at the library, supplanted now with online versions (many community powered) such as Choose Your Story, Choice of Games, or this list from DMOZ. Please note that I am not attesting to the quality of any of these sites, or the appropriateness of the content, as some come with explicit disclaimers about not being for children. Still, the idea of creating hypertext with branching storylines in the “choose your own adventure” style is one that makes a good deal of sense, especially for students in elementary and middle school. This is certainly one model of interactivity.

Another potential example would be to create hypertext fiction. Described on Wikipedia as “a genre of electronic literature, characterized by the use of hypertext links which provide a new context for non-linearity in literature and reader interaction,” hypertext fiction can include words or images that are linked to internal pages of a website or out to different sources. Again, as a genre that would be relatively easy to produce in the form of an e-book, students could use principles of hypertext fiction to link to additional content that they create and present inside of the e-book, as well as to external sources. This set of 100 Flash Fiction Hypertexts appears to be a good place to find some examples.

Finally, I would look to the example of Scratch, a tool that students can use to “program your own interactive stories, games, and animations.” I was fortunate enough to visit the MIT Media Lab last fall while in Boston for NCTE, and as someone who had only tangentially known about this tool, I’m simply amazed at what Scratch can do. In particular, as a storytelling tool, Scratch provides options for interactivity as well as numerous examples created by users in their community. Many of the same types of functions that would appear in an interactive ebook are available in Scratch, so it provides a good space for students to learn, play, and explore.

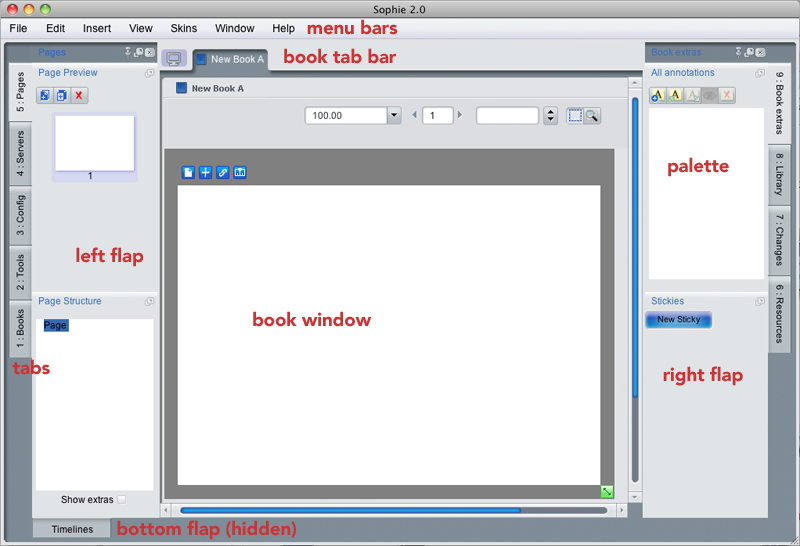

Tools for Creating Enhanced eBooks

Beyond the examples listed above, there are a number of tools that we can use to construct interactive e-books, or at least websites that would function in a similar manner. I suppose that I don’t get too picky here because, given that I am trying to present a wide variety of tools and options, whether or not something is presented in a downloadable e-book format or available on the web seems to matter less than the actual quality of the writing. For teachers, my strong inclination is to use web-based tools to create these kinds of enhanced texts, yet encourage students to move beyond short and simple pieces into lengthier, more nuanced, and complex ones.

So, one possibility that I think many of us might overlook is the idea that we could create a simple slide presentation, using words, images, or invisible shapes on the screen to act as hyperlinks. There are of course the free Open Office Impress and Google Presentations which are popular tools, and Cool Tools for Schools lists even more. There are a number of other tools that would allow students to create some level of interactivity such as Booktracks (adding a sound track to a written text), Voicethread (for commenting on text, images, or video), or Meograph (which invites users to create stories with various media elements). Recently, I was introduced to a new tool, Play, which allows users to “ curate emotive multimedia content, stimulating peers to create, circulate, and interact through new media.” And, finally, I have heard about, but haven’t really tried Inklewriter for Teachers, a tool that allows students to create stories that require the reader to make choices, much like the Choose Your Own Adventure idea noted above.

Conclusion

With this post, I end with a few questions for us to consider:

- As we think about the affordances of enhanced ebooks, how can we help students think creatively about telling stories, presenting information, and making arguments?

- What do we feel could be a useful way to encourage the remix/reuse of existing media as we create ebooks?

- How might we invite them to make their own media that could enhance their ebooks?

We want our digital writers to think about enhancement in ways that move well beyond the bells and whistle, inviting their readers to use these features as a critical component of meaning making. My final post later this week will look at the last category of ebooks: enhanced ebooks, in which interactivity and multimedia are, indeed, central to the comprehension process.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Like this:

Like Loading...