Tomorrow, I have the privilege of keynoting the Eastern Michigan Writing Project’s fall conference, “Writing Beyond Expectations.” I have been giving a great deal of thought to the event, and as both a teacher educator and writing project director, have been trying to figure out how to frame my talk in light of the conference theme. Content standards and expectations, of course, come to mind when I first consider this theme, yet I have been thinking more and more about the expectations, both tacit and explicit, that we have of ourselves as teachers of writing and, equally important, that we have of our students. So, with that in mind, I am going to think through this idea of “writing beyond expectations,” especially in light of digital writing, through these three lenses: our content, our students, and ourselves.

Writing beyond content expectations

As we consider the many pressures exerted on us from state and now national content expectations, certainly we could feel angry, frustrated, confused, or downright indignant about the fact that, without much input from educators, we have had yet another set of standards put upon us and our students. And, while political opinions on this abound, I want to think for a moment about how we can use the new core standards as a place to begin, a place from which we can write beyond the expectations. In particular, I am interested in exploring how the three genres represented in the standards– argumentative, informative, and narrative — can be enhanced by digital writing.

Argumentative expectations include clear statements of one’s claim, evidence of support, and acknowledgment of counterarguments, and digital writing tools can provide opportunities for students to present their work in this mode through a variety of media. For instance, we can invite students to create podcasts in which they perform a dialogue — perhaps scripted, perhaps not — where they present their side of an argument and engage in conversation with someone holding the opposite view. We can invite them to post public service announcement videos on YouTube or Viddler, then annotate those videos with comments about effectiveness of the rhetorical strategies the writers have used. We can also invite students to create VoiceThreads around a particular topic, or engage in conversation through a social network or blog.

For informative writing, students are expected to examine a topic and support it with relevant details, including domain specific vocabulary. We can invite them to create hypertexts — via blogs, wikis, or websites — where they divide up their information into sub-pages, thinking about about when and where to insert hyperlinks to both connect their own pages and link to others. In those pages, they can think about how additional audio, video, and images can be used to provide support for the information they are trying to present. Also, we can teach them how to research with RSS and advanced search, as well as how to cite their sources with social bookmarking and online citation tools.

Narrative expectations also provide us with opportunities to explore digital possibilities, including ones to develop dialogue, characters, setting, and the arc of a story by blending words, both spoken and written, with images, music, and sound effects. Modeling a narrative in a manner similar to stories that one might hear on This American Life would be one option to pursue if using podcasting. Also, digital storytelling provides students ways to create multimedia videos that build from the mode of memoir, where the whole story really becomes more than simply the sum of its media parts. Other narrative examples that I have seen include a choose your own adventure story that has grown organically on a wiki, or the use of tweets or status updates that tell a story.

All of this is just to say that when we invite students to write beyond content expectations — considering the different ways in which we can represent argumentative, informational, and narrative modes through different media — we will give them opportunities to express themselves in different ways, always considering the audiences and purpose for their writing. Which leads next to helping students as they learn to write beyond themselves.

(Students) Writing beyond themselves

When we ask students to write, we certainly want them to meet our academic standards, yet we also know that they are trying to learn how to be writers and, perhaps even more importantly, reply to the writing of others. In this sense, we need to expect that students will write beyond themselves. By this, I do not mean that students will necessarily try to write more lengthy, complex pieces than what they are ready for, although that can sometimes present them with welcome challenges. Instead, what I suggest here is that students write beyond themselves first by focusing on external audiences and purposes and, second, by learning how to respond to others, especially through digital means.

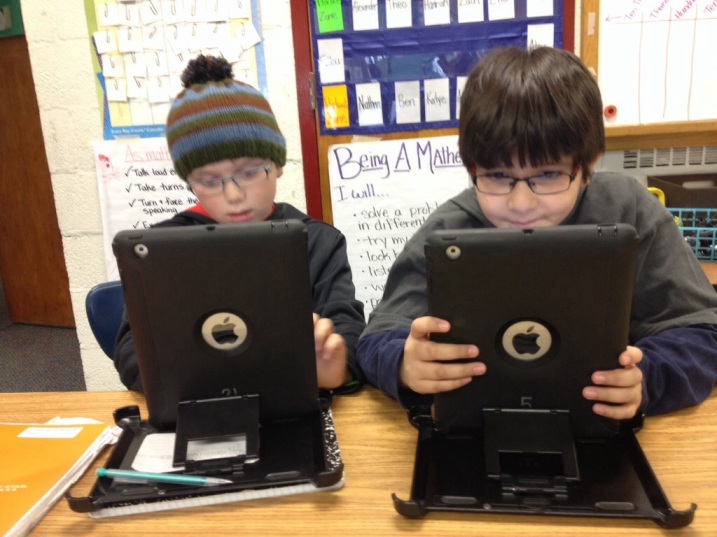

First, I believe that students should write for external audiences, as all teachers of a writing workshop approach have advocated for over the past few decades. That said, the internet makes these external audiences much easier to communicate with, although it is not enough simply to have students post to a blog and call it good. Cultivating a community of digital writers is a task that teachers need to take seriously, which leads to the second point. A digital writer needs to be both a writer and a responder. When trying to learn about their audience, students should take the opportunity to get to know them by reading what they have written and then engaging in response. Fan fiction communities, where veteran writers mentor newer writers are a great example of this. Moreover, it is nearly as easy to respond to a digital text through talk as it is through type. Digital writing happens, in large part, due to the fact that it occurs in a network (or across networks), and expecting that students will write — and respond — beyond themselves is of critical importance for them as they become digital writers.

Writing beyond ourselves

In this sense, we want to build on our long-held belief that teachers should be writers, and expand our understanding of who a teacher as writer actually is. What does it mean for us, as teachers, to be writers? To be digital writers? Teachers who write make better teachers of writing and, in turn, teachers who are digital writers make better teachers of digital writing. Yet, if digital writing is scary in and of itself, then teaching digital writing is probably even more of a frightful leap for most of us. Not only because we feel that we want to be “in charge” of our classroom or that we want to look nothing less than knowledgeable in front of our students, but because understanding of what digital writing is, and what it can do, is limited both by our own experiences as writers, as well as the resources present in our schools and classrooms.

In the past few years, and even in an online conversation I have facilitated this month, I have heard nearly every reason why we shouldn’t teach digital writing — from issues related to the digital divide to the lack of time we have to cram yet another thing into our curriculum to concerns about filtering and our inability to get to websites and install programs on our computers. I hear, and understand, these concerns, yet my response now — even more so than what I would have been comfortable saying just a few short years ago — is that we need simply to move forward. Even two years ago, I would have had trouble making the claim that students could have access to a word processor outside of school and be able to save their work whether they are at school, at home, at the library, or on their mobile phone. But, now, nearly all of them can. In short, we are at a point were access is, quite nearly, ubiquitous when we use cloud computing applications, and I don’t think that we have any excuse anymore for not engaging students in digital writing.

Also, we need to ask ourselves, “What does it mean to be a writer in a digital age?” When and how do we use images, sounds, and music to support our arguments, descriptions, and stories? When do we post to a blog as compared to a wiki? Why would we want to use either, or would we want to use something else instead? In what ways can we think about our own writing practices — from emailing and texting, to writing letters and lesson plans — and how we use digital tools in a variety of ways to draft, revise, and publish our work?

As we think about our content, our students, and ourselves, we need to learn to write beyond our own expectations. We need to think about the ways that we ask our students to be digital writers by being digital writers ourselves. As we turn our attention to your classrooms throughout the rest of this conference, I invite you to think about how we can write beyond expectations as we compose our classrooms, and craft our digital writing workshops, both today and as technologies, students, and our culture continues to change.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License.

Like this:

Like Loading...